Skidmarks – Riding Home

“…Combat is like unsafe sex in that it’s a major thrill with possible horrible consequences.” —Carl Marlantes, What it is Like to go to War

Here’s a Veteran’s Day thought that’s a bit late for Veteran’s Day: The most plausible origin of the term “squid,” as it refers to unskilled, risk-taking motorcyclists, is that the already in-use pejorative (as applied by U.S. Marines, who are in-turn called “jarheads” by sailors) described sailors back from Vietnam who strafed Southern California backroads and freeways on Japanese two-strokes with predictably messy results.* Forty years on, not much has changed: in 2008, more Marines died in motorcycle crashes than in combat in Iraq, and the DoD has since instituted mandatory safety programs like the one run by Lee Parks.

If you’re a combat veteran, I shouldn’t have to explain why young men (I can’t speak for young women, who have their own story to tell) returning from war often feel the need to continue to risk violent death. I’m slightly embarrassed by my own combat-veteran status—calling Operation Desert Storm a “war” is like calling a Fun Size bag of peanut M&Ms a multi-course meal because it has one green M&M in it—but even the heroes (and I’m only using that overused word because I can’t think of a better one) who have gone to Iraq and Afghanistan for tour after endless tour don’t talk much about the geopolitical achievements of those conflicts, even if there are any.

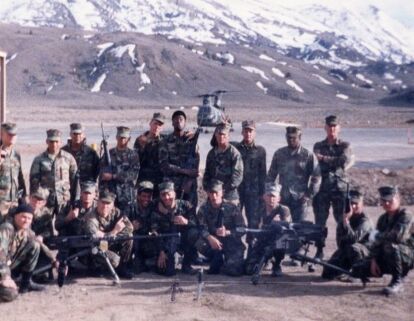

What we do talk about are the bonds we made. Serving in combat together creates a relationship like no other. You’re closer to your battle buddy than to your girlfriend, your brother, your best friend from childhood. It rivals the bond you feel for your own children. “Individual possessions and advantage count for nothing: the group is everything,” writes Vietnam veteran and screenwriter William Broyles Jr. in his 1984 essay, Why Men Love War. “What you have is shared with your friends. It isn’t a particularly selective process, but a love that needs no reasons, that transcends race and personality and education.” I could tell you intimate details about the marines and sailors I shared Humm-vees and bunkers with, and I know that I could sit down with any one of them and like an old married couple, it would be as if we had seen each other yesterday.

Another thing you’ll hear vets mention—if you buy them enough drinks—is the mind-altering clarity of war. One morning in 1991 I crawled out of a damp sleeping bag to gaze on thousands of Marine Corps armored vehicles, deployed in the Kuwaiti desert and poised to crush one of the biggest armies on Earth. The mailed fist of the modern industrialized world stretched out as far as I could see, tanks and amtracks and trucks and the tiny black dots of grunts slogging through oil-soaked sand. The night before, one of our truck drivers was killed by an anti-tank rocket, and several more Marines were wounded. I didn’t care. I’m alive, I thought, gazing into a horizon black with smoke and dotted with burning oil wells. Nothing else matters. For an instant, the world was sharp, focused and logical. I was alive, we were going to win, and then I would go home.

Like many combat vets, I didn’t want to remain on active duty, yet I pined for that brotherhood and simple clarity. I found those things in San Francisco’s motorcycling community, and soon was in a new platoon of like-minded riders. It was as if I had never stopped being a jarhead—each Sunday I’d gear up and combat the winding, high-speed roads of West Marin with my skilled and fearless comrades-in-arms. Stakes were high: many of us were killed or severely injured, and it was a constant cat-and-mouse game avoiding law enforcement.

I soon discovered amateur roadracing with the AFM, a Northern California roadracing club. Like the Marines, the AFM was an elite organization, an incubator for top racing talent like Don Vesco, Reg Pridmore, Eddie Lawson, Wayne Rainey and Steve Rapp. Even racing the slowest class, 250 Production, was hyper competitive and as intense an experience as being at the wrong end of an artillery barrage. Sixty-five Ninja 250s, engines buzzing like a swarm of angry bees, charged an 18-inch race line in Sears Point’s Turn 2, and nobody was going to be second. Like combat, racing was hours and hours of drudgery and boredom—endless last-minute engine rebuilds, watching race after endless race until yours was called—punctuated by a few 20-minute races, 8 adrenaline-drenched laps where nothing, not even life and limb, was more important than passing the racer ahead of you.

Like wartime, nothing was more important that completing the mission. We burned gas, tires, money and entire engines like we got them for free. If the check-oil lamp came on and there was less than a lap to go, I’d pin it and hope I didn’t seize up the main bearings before the checkered flag came down, even if I was only battling for 18th place. In an actual war, the government is writing the checks for equipment and medical treatment, which is why racers look for sponsors.

War is a game for young men, and as I’ve aged the competitive spirit in me has faded. Hopefully, I’ll never find myself once more seated behind a .50 cal atop a Hummvee as it bumps its way through a minefield, and I no longer feel the need to max out my Capital One card to buy a steering damper and shave one more tenth off my best lap time, or buy yet another used engine on eBay “Original owner! Only synthetic oil used! Sorry, no paperwork!”

I may not be able to get together with my old Marine Corps comrades and re-invade Kuwait (though Vegas might be an acceptable substitute), but I can still meet up with my old riding buddies and bend a basic speed law or two on Sunday mornings. In Kuwait, I survived through luck, training and the sacrifices of my buddies (but let’s face it, it was mostly luck and an overwhelming military advantage). Sailing around a blind corner on Highway One, luck, skill and faith that if the guy in front of me made it, I can too gets me to breakfast alive.

And sitting there with my eggs and toast and steaming coffee while guys I trust my life with laugh and talk, I know I’m home. Let’s hope next Veteran’s Day, we’re all home, alive, laughing about our close calls.

*Yes, I’ve heard all the other etymological theories, so unless you have a credible and scholarly source to share, please shut up about this. I find the contraction (“squirrely kid”) and acronym theories particularly tedious and unsupported.

Gabe Ets-Hokin lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and supports the legalization of marijuana, but only at same-sex multiple-partner weddings in Utah.

More by Gabe Ets-Hokin

Comments

Join the conversation

Yes, killing people does require cooperation, as does staying alive as a rider/racer. And, as we've seen lately, an "overwhelming military advantage" can be a decisive advantage. An unarmed adversary helps as well. But hey, I'm down for that invasion of Vegas. Hayduke Lives! Then we can catch one of them Utah weddings.