Head Shake - The Kid and the Garage

A lot of things get fixed in a garage, not all of them mechanical. I’ve come over the years to be convinced that a garage is an essential part of being a whole human being and a vital member of the community, any community you wish to be a part of. Sure, there is the obvious: working in a garage is preferable to squatting in a mud puddle in a gravel driveway in February. But there is more, much more.

Garages can serve as meeting places, social focal points, and an open garage door signifies to the world that you are home and working on something. A garage makes you more accessible. This can be troublesome at times, but the rewards can be enormous because there are many things to fix or improve in this world, not all of them with torque wrenches, shop manuals, and feeler gauges.

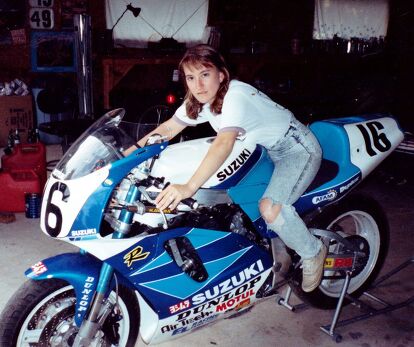

When we first arrived in Ohio we had little time to find a place to live. My criteria were few: I wanted rural, and I wanted a garage. I was told it was difficult to find anything on short notice and we should consider ourselves lucky for anything that turns up. We got lucky, very lucky. We found an old one-room school house with a perfect garage that evolved over time into “The Temple of Speed.” In all honesty, I can’t really say how much speed came out of there, but I know a lot of good came out of it.

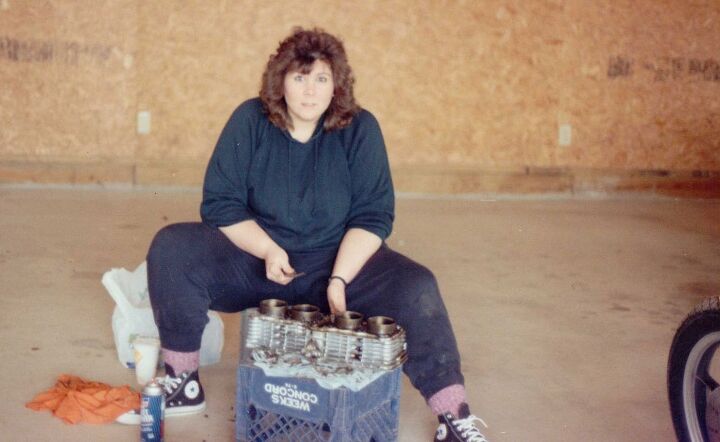

We no sooner had moved in, and I had barely started working at the AMA when a co-worker’s bike, a KZ1000, began leaking oil like a sieve. Its owner was a hard-working woman in my department and didn’t have a bunch of money to throw around. I had the requisite knowledge of Kawi big bores, a buttload of valve shims, the cool guy valve tools, and I had been inside a few of these things before. So the requisite invitation was offered: “Bring it on over. Let’s see what we can do about this.” And she did.

We worked on it together. Parts went off to the machine shop, other parts got ordered, and we put everything back together like it should be. She continued for a number of years to do what she always did, which was ride the wheels off the thing, until she sold it for a new ride. Not to be one to discriminate, and looking for a reason to justify carrying around all these SAE tools for all those years, we did the same for a coworker’s Harley.

But the best project to ever come out of that garage was a neighbor kid named John. I recognized this kid was a motorhead, and clever, and always up to something. But he put the under in underachiever. He had little interest in school, which, to listen to him tell it, had little interest in him as well. He’d get in fights in the school yard; the principal knew him by name. When he saw my garage door open, he’d wander over and hang out, watch over my shoulder whatever I was doing, and try to steal beer out of the garage fridge. I recognized this kid from years before: he was me.

This went on for awhile, and I genuinely liked the kid and his family – they were really good people. He was hanging out one afternoon while I was wrenching on something, helping grab tools and whatnot, and he was talking about school again and everything going wrong. I guess I had just had it, so I told him the truth:

“Look, John, you are a bright kid, smart as the day is long, and you can get all the respect you want on the schoolyard getting in these fights and all. But if you are an idiot in the classroom? You will get no respect at all. No respect from your teachers, no respect from your classmates, none, zero. You can do better than this. You’re a smart kid. Don’t do this. You have to earn that respect in the classroom and out in the schoolyard. Everybody wants you to win – your teachers, your parents, and me, all of us.”

I told him not to do it the hard way. I had a buddy growing up who was smart, smart enough to do it the easy way, the path of least resistance. Exhibit some effort, get decent grades, make your parents proud of you, most colleges would accept you, you’d be labeled a good kid all the way up, that was the way to fly. Not the hard way, always clawing back from behind – that’s like stalling on the start line. Don’t end up dropping out of high school and joining the Army like some knuckleheads I know (and he knew too, that bad example was standing right in front of him talking to him after all).

He thought about it and came back the next day and said, “Okay, well, where do we start?” The garage had a new job.

At this point you are probably wondering what any of this has to do with bikes. It has everything to do with bikes – the garage, the kid, the whole thing. If it hadn’t been for bikes, and me wrenching on them, racing them, bump-starting them in front of his house at all hours, and riding them, I never would have established that relationship with John. He never would have borrowed my Gericke leather pants to wear to some school deal with his Jim Morrison t-shirt (that still cracks me up). I wouldn’t have been “cool” enough to even talk to. Boys like bikes and speed – this is a universal truth.

So, I made a deal with him: I’d call the cadence; he’d call the exercise. He was going to keep a journal, the subject matter was dependent upon what he had read the day before, which we would then discuss. I still had all my books and notes from my undergrad education, four years worth, and I would treat him just like a starting undergrad at one of the better liberal arts colleges in this country.

He would read – a lot – and I knew he’d eat that up; he was naturally curious and sharp. His math was good, but my wife was pursuing a masters degree in education at that point, so, push come to shove, she could handle that. We established a routine and stuck to it, and I promised him one more thing to sweeten the pot. “Look around, see anything you like?”

I thought he’d go for a bike, my wishful thinking maybe. No, he looked at my Mazda RX-7, a car of course. “Okay, if you graduate with a 3.5 average from high school, that car is yours. Deal? You can do this.” He chuckled.

“I’m not kidding here, deal?”

It was a deal.

We had a couple years to work with. He was failing almost everything, but we had time, and he put his head down and charged. I never had kids, and I never thought about hanging report cards on the refrigerator. Suffice it to say, when he showed up beaming about his report card, we started doing that. He did outstanding. The teachers saw him genuinely making an effort and worked with him. Over time, that curve came up, and he’d come home proud of that report card: As and Bs. I’d be lying if I didn’t say I wasn’t proud of him too. He graduated high school but came up just short on that 3.5 average.

I wrestled with the right way to deal with that. Fold and give him the car? He really had exceeded all expectations. Or stick to the rules? I really didn’t care about the car at this point. I’d always been straight up with him; he didn’t make the cut. So, I told him I was sorry, but I was damned proud of him. He had done good. In my gut, I really hoped he wasn’t disappointed. I was truly proud of him and what he had accomplished. Then I saw he really had learned something and couldn’t care less about that car. He’d gone from failing to becoming one of the better students in the school. Maybe we all learned something.

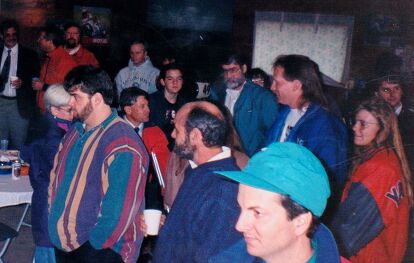

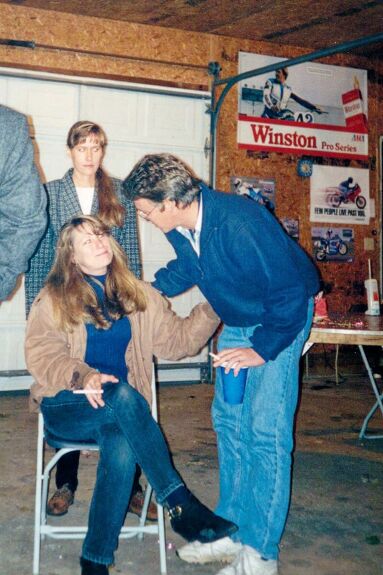

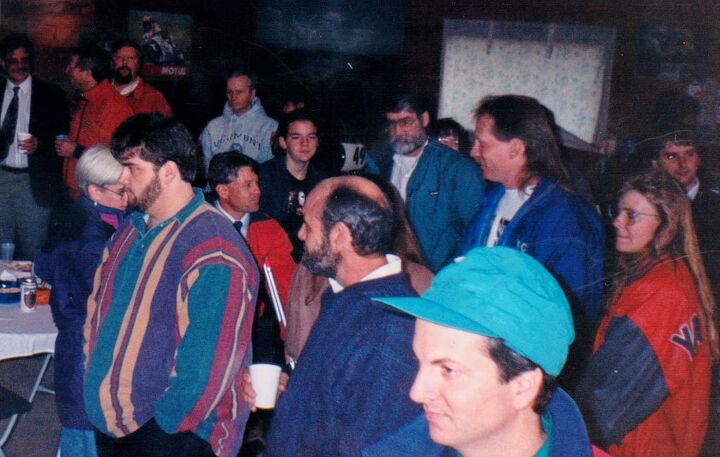

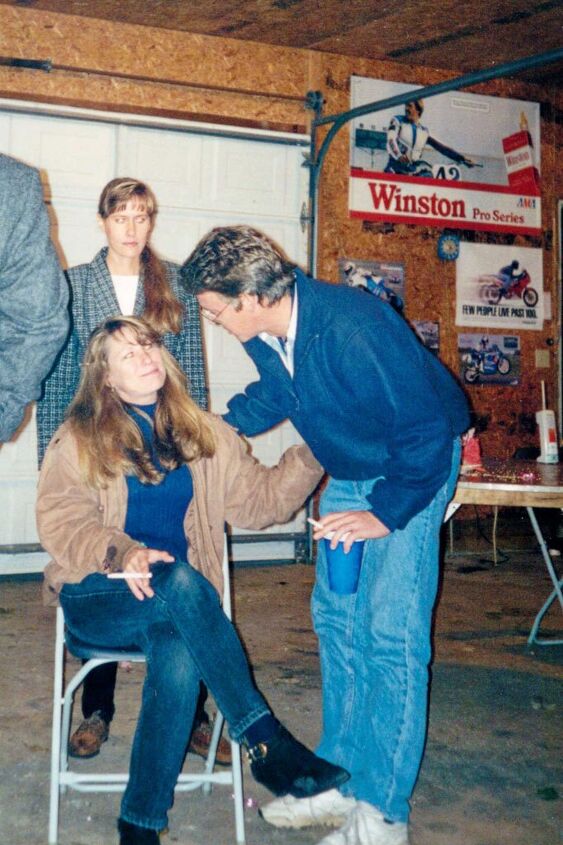

That garage was at alternate times used to work on everything from Harleys to Kawis to countless race bikes, a Ford Econoline van race hauler, a buddy’s 5.0-liter Mustang, and my old, tired Toyota pickup that knew its way by memory to every track on the East Coast and upper Midwest. It was a counseling center for a friend whose husband was killed in Columbus, Ohio, and the meeting site for a wedding reception. It was a school and a refuge for kindred spirits. It was a place to console others in times of need and a place to fix things.

A lot of people and things move through a garage and move on, hopefully better off than they were before. They say a man’s house is his castle. I disagree. A man’s house is a pain in the ass that always needs something that usually involves writing a check. A man’s garage, though, that is the castle where stuff gets fixed.

About the Author: Chris Kallfelz is an orphaned Irish Catholic German Jew from a broken home with distinctly Buddhist tendencies. He hasn’t got the sense God gave seafood. Nice women seem to like him on occasion, for which he is eternally thankful, and he wrecks cars, badly, which is why bikes make sense. He doesn’t wreck bikes, unless they are on a track in closed course competition, and then all bets are off. He can hold a reasonable dinner conversation, eats with his mouth closed, and quotes Blaise Pascal when he’s not trying to high-side something for a five-dollar trophy. He’s been educated everywhere, and can ride bikes, commercial airliners and main battle tanks.

More by Chris Kallfelz

Comments

Join the conversation

Great story, but I'd like to hear more about the 5.0 Mustang GT.

Great read! Loved it!